Mum’s the word

The mom mania on the small screen can be traced to the surefire success of mother-fixated films like Mother India and Deewar, writes Nirupama Dutt

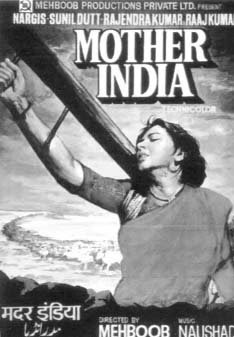

Nargis in Mother India upholds dharma by killing the son she loves the most (Sunil Dutt)Amitabh Bachchan is left speechless when Shashi Kapoor tells him “Mere paas ma hai”

The Mother India myth has been one of sure success in Hindi films. Popular Indian cinema is indeed mother-centric with a host of graceful matriarchs having done honours to the Indian screen from Durga Khote, Leela Chitnis, Nirupa Roy, Sulochana to Nutan, Waheeda Rehman and Rakhi. The famous dialogue from the Amitabh Bachchan blockbuster Deewar is still repeated. Amitabh, the baddie, tells Shashi Kapoor, the goodi-good younger brother, "Mere paas bangla hai, gadhi hai, paisa hai. Tere paas kya hai?" Pat comes the reply, "Mere paas maa hai."

Mama-mania is a way of life in the Indian cinema and it succeeds many a time. But the man who gave the archetypal Mother figure to the Indian screen was the great filmmaker Mehboob Khan in Mother India in 1957. Mother India was a remake in technicolour with a brand new star case of Mehboob’s earlier Aurat (1940). Iqbal Massod once writing on this archetypal mother said, "The mother upholds the dharma which the good son follows. When the bad son transgresses it, he is killed." The ever-lasting myth of the big screen has been providing a catharsis to audiences as they sit every night at half past ten to watch Kyunki Saas bhi Kabhie Bahu Thhi. Smriti Irani, playing Tulsi Virani in the serial has done the Mother India act with aplomb by killing Ansh and winning the approval of the viewers.

The mother figure in the Indian psyche is different from that in the West. Julia Glancy, a Britisher and wife of a pre-Partition Punjab Governor once during her stay in India remarked in surprise, "The strongest relationship in India is between mother and son and not husband and wife." To the Indian mind, deeply entrenched in the concepts of Mother Earth and Mother Goddess, there is nothing strange or surprising about this.

They do not have the Freudean theory of the Oedipal complex to bother about.This concept has been liberally splashed in popular art, including calendars, posters and advertisements.

When Mehboob made Aurat in 1940, it was the time of the national struggle against the colonial rule. Mehboob combined in his creation of the mother figure the two concepts of Mother Earth and Mother Goddess. The film thus gave a vigour to the national movement as this was the time when posters were being printed of Bharat Mata in chains and suffering. Or martyrs like Bhagat Singh offering their heads to Bharat Mata. Post-Independence India saw the image of Bharat Mata with her chains broken, the tricolour on the border of her sari and a smile on her face to encourage her favourite son Jawaharlal Nehru.

It was in the renewed scenario that Nargis was reborn as Mother India, striking a famous pose with the plough on her body. To save the honour of the village, she even kills her son, played by Sunil Dutt, who turns a dacoit and is making way with the wicked money-lender’s daughter. She kills the son she loves the most for she upholds dharma.

People just loved it and the film has the reputation of running till date in one cinema hall or the other in the country and still attracting audiences.

Every decade has seen one or more films which played with the myth in one way or other. It was Ganga Jamuna in the 60s, Deewar in the 70s, Ram Lakhan in the 80s, Vaastav in the 90s and Koi Mere Dil Se Poochhe in the new century.

And now the small screen has appropriated this myth giving Tulsi Virani the greatest status that the Indian imagination can envisage. Women in the neighbourhoods are talking of little else and when the story was leaked out a couple of weeks before the trigger was actually pulled, it made front page news in national dailies.

So the moral of the story is when all other formulae fail, it is best to have a good mother and an erring son. Mama mia! A killer mother never fails for the Mother India myth is forever.